t last May’s GemGenève, we bumped into a well-known jeweller coming out of one of the stands. “I just bought some diamonds from Taché,” he told us. “They’re the best anywhere.” For a journalist, sitting down to chat with a diamantaire is pretty much mission impossible, but the door to the Taché stand was open so… why not go in? We left a few minutes later with an appointment to meet Jean-Jacques Taché. This specialist in exceptional stones belongs to the third generation of a family of diamantaires who began a jewellery business in Damascus, Syria, in the early twentieth century, relocating to Antwerp in the 1950s.

In less than three generations, Taché has become a globally recognised group whose activity is divided into three departments. One deals in melee diamonds, supplying small stones for pavés; a second supplies certified diamonds between 30 points and three carats, and the third main department specialises in rare, exceptional diamonds of over three carats.

Taché is a familiar name to everyone in the diamond business. Mining companies have their language, jewellers have another and Taché is the bridge between the two. The group is on the De Beers Global Sightholder Sales (DBGSS) list of buyers which have access to De Beers rough diamonds at events known as sights, which take place ten times a year. It also buys from other miners. Thanks to its reputation and expertise, Taché is in a position to acquire such rare rough diamonds as the 342-carat Queen of Kalahari in 2015 and the 910-carat Lesotho Legend in 2018, at that time one of the five largest diamonds in the world. Both gave rise to stunning jewellery collections, the former by Chopard and the latter by Van Cleef & Arpels.

-

- Jean-Jacques Taché is a specialist in exceptional stones.

“Being a sightholder doesn’t mean we only buy large stones,” Jean-Jacques Taché told us as we sat down for our interview. “We also purchase smaller stones that we produce for every category of diamond our customers require.”

Europa Star: What role does Taché play as a facilitator between the mine and the jeweller?

Jean-Jacques Taché: Taché is headquartered in Antwerp and was established in 1957. I belong to the third generation of a family who arrived in Belgium, from Syria, in the 1950s and who gradually moved out of jewellery-making to focus on diamond trading. Today’s Groupe Taché has a range of activities. It is a respected manufacturer for the biggest mining companies and leading jewellery houses. It has been a De Beers sightholder for over 30 years. De Beers used to distribute 80% of roughs but that has fallen to 35% in today’s more fragmented market, meaning we now also work with more junior miners who sell their stones.

-

- A 79.35-carat, D-FL Type IIa oval diamond, the largest of the 67 stones cut from the 910-carat Lesotho Legend.

- ©Ilan Taché

Are there mines you don’t work with?

We buy from virtually every mine that is approved and certified by the Kimberley Process. As I mentioned earlier, our core business has always been trading in polished diamonds and that was the group’s main activity in the 1960s and 70s. Since then, our model has changed to become a vertically integrated manufacturer. We source rough diamonds from the mining companies which we then polish and distribute to our customers and the market. We manufacture the vast majority of our diamonds, however from time to time we do still buy polished stones from audited suppliers who guarantee their origin and traceability. This way we can meet all our clientele’s requirements.

Is it simpler for you to buy roughs as opposed to cut diamonds?

Yes, because a rough diamond comes with a document attesting to its origin and has complete traceability, so we know where it was mined. When you buy a polished diamond, it is best you know who you are buying from.

As a sightholder, are you the first to be informed when an exceptional rough diamond has been found?

Being a sightholder doesn’t give you access to this information; your reputation does. Whenever you buy an exceptional stone at source, whether directly, through a mining company or from a junior miner at auction, you add to your expertise and your reputation grows.

Our job is to promote the products of the mining companies among the leading jewellery houses and to assist these houses in sourcing the rare diamonds that will become landmark jewellery collections. The capacity to accompany an outstanding stone all the way from the mine of origin to its transformation into beautiful jewels makes you a partner of choice. To give an example, when a mining company extracts an exceptional rough stone, they invite three or four diamantaires to view it and make an offer. Taché is usually one of them, because it has already collaborated on often well-publicised projects and because it maintains close relations with leading jewellery houses.

What happens once you have viewed a rough?

You should always allow two to three weeks for viewing: the time it takes for us to examine the rough diamond, go back, look at it again, and for the other companies to do the same, before possibly making an offer. During this time, we’ll talk with several potential customers. Some may show interest, however it’s rare for anyone to commit to buying a rough stone up front. Then there is always the final hurdle of price. The stone will sell to the highest bidder, so even with the backing of a major jewellery house, there is no guarantee we will win.

Would you purchase a rough stone without first securing the potential interest of a jeweller?

If it is a truly exceptional stone, we’ll take the risk and put in an offer. We work on the assumption that jewellers must see and physically handle a stone in order to imagine how they could incorporate it into their collections.

-

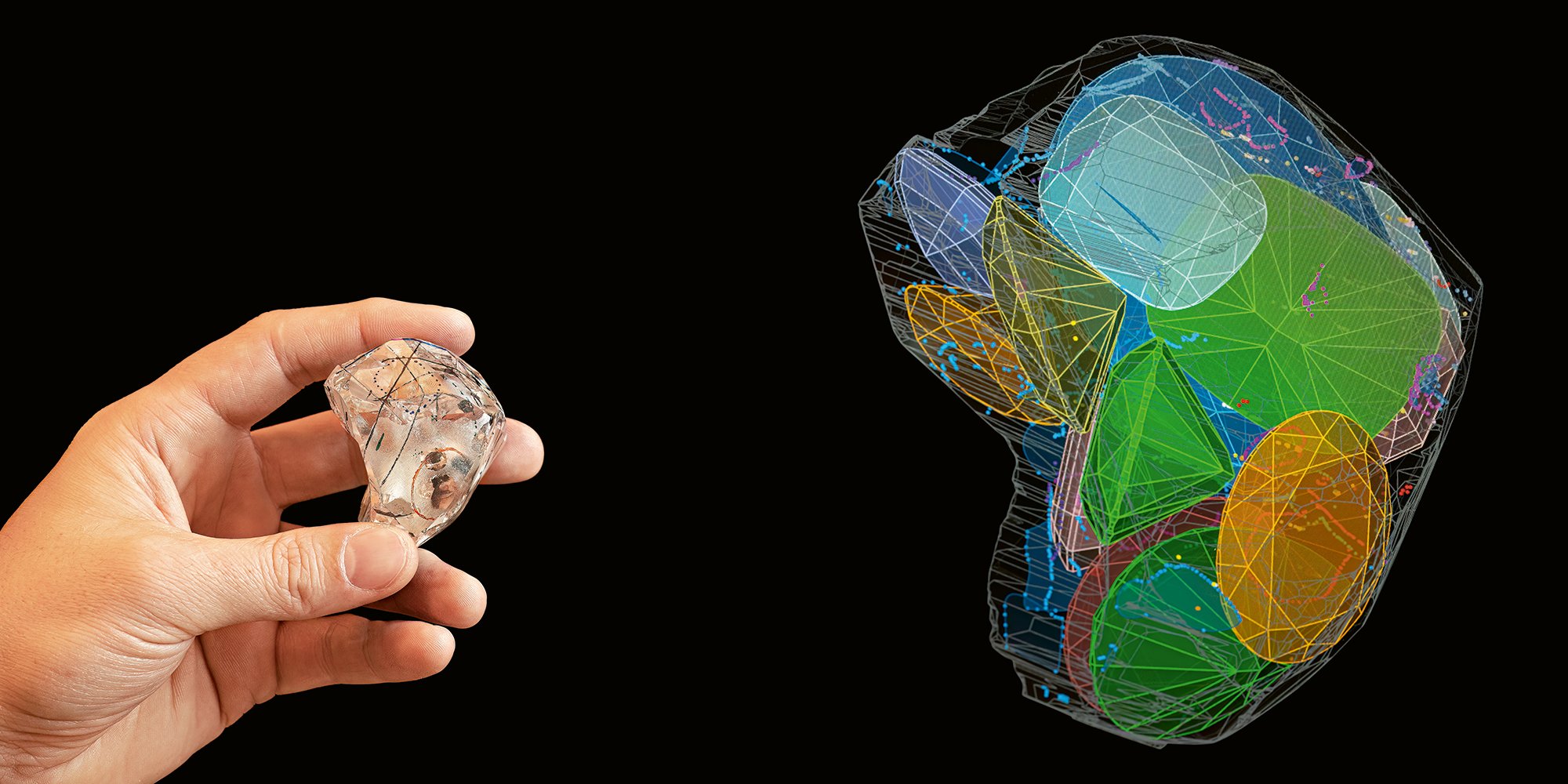

- Marking the Lesotho Legend prior to the first cuts

Which is the biggest acquisition you’ve ever made, without having a buyer in the wings?

In March 2018 we acquired the 910-carat Lesotho Legend, one of the largest rough diamonds ever, without a jeweller backing us. We did something very unusual and decided to show it at Baselworld. This was the first time anyone had ever exhibited a large rough stone. It truly was an impressive diamond, like nothing any of us had ever seen or held before. It was the talk of Basel! We had representatives from all the major jewellery houses coming to see it, including Van Cleef & Arpels who ultimately bought the stone. The CEO at the time wanted to build a unique collection around this single rough diamond. He asked us to start analysing it and to scan it and show him a polishing plan. It was a remarkable collaboration with both parties pooling their knowledge and expertise. Our analysis of the stone had to consider factors such as the customer’s preferences, limits, shapes they liked or did not like. It was a beautifully orchestrated score, played to perfection.

You gave the Lesotho Legend to Diamcad for polishing. Are they your go-to partner for exceptional stones?

Whenever you have a project that involves an exceptional stone, you have to know who you want to polish it and we have been working with Diamcad for many years. In the diamond industry, it’s essential that you have complete faith in your partners at every stage of production. Diamcad also helps us analyse stones at the buying stage. For the Lesotho Legend, I was getting calls from manufacturers all over the world. Some were even prepared to polish it free of charge! You need to remember that polishing a stone like this is extremely complex. We didn’t have a moment’s hesitation. Firstly, the manufacturer had to be located in Antwerp. You can’t send a diamond like this halfway round the world. You must physically be close enough to be able to go to the manufacturer’s premises, monitor every stage in production and give the go-ahead each time. Even after state-of-the-art technology has defined a plan and calculated the shape, size, etc. of the polished stones, the trained eye is vital to the rest of the process. For projects such as this, the work of the diamantaire is as much science as it is art.

What was your priority when cutting this 910-carat rough diamond? To yield as many carats as possible?

No, our objective wasn’t to maximise the weight. We could probably have sent it somewhere else and obtained an additional four to ten carats, because it really was a large stone, but we had a different perception. We looked for the solution that would satisfy our customer and yield stones that met their criteria and tastes, in their preferred shapes. We could have used more of the rough stone had we opted for different shapes, but that was not the direction we chose to take.

-

- Making the first cuts in the Lesotho Legend

What was it like before rough stones were cut with the benefit of modern technology?

Technology is constantly evolving. I started cutting large stones around the year 2000, when there was some technology but nothing as developed as it is today. Forty years ago, we did not use computers. If we’d had a 910-carat rough diamond then, we would have aimed for the largest stones possible, hence there would have been fewer of them. Cutting a rough diamond was always one step at a time: we’d cleave the stone, spot a problem, adapt the solution. The Lesotho Legend would never have yielded the 67 stones that became an entire collection of jewellery. Today we spend longer analysing a stone than we do polishing it. The Lesotho Legend took twelve months to analyse and six months to manufacture. Once a rough stone has been analysed, mapped and we know exactly how it will be polished, there are no surprises. Scanning a stone is like completing a puzzle; we know exactly what the finished picture will be. Given the financial implications of a project of this importance, any problems must be resolved from the outset. We then make full-scale glass replicas of the cut stones so that the jeweller can start work on the collection before taking delivery of the actual diamonds.

Is intuition still part of the polishing process?

Analysing a rough is part technology, part intuition, but the second you start the manufacturing, there can be no room for intuition. The plan is, dare I say, set in stone. Which doesn’t take away any of the magic of what we do.

-

- The Lesotho Legend after the first cut

What type of problem might you encounter when cutting a rough stone?

Invariably there are complications. You can cut some stones like a knife through butter, but it’s rare. You might find an inclusion which you thought was less than five microns and which turns out to be slightly larger. If we leave it, the stone will no longer be Flawless but VVS1 [very very slightly included], so it has to be “neutralised” and this means rescanning the stone. It’s all part of the game. Sometimes natural elements appear, such as graining [lines formed inside the diamond due to irregular crystal growth] which affects clarity, or a diminution in colour. Things we can never entirely eliminate.

To what extent can technology make cutting a risk-free process?

There is no such thing as zero-risk, but we do try to reduce risk to a minimum before we start cutting. This is another reason why it’s important to know where a stone was extracted. For example, we know that the Letseng mine in Lesotho produces a high number of rough diamonds that become D-Flawless IIa diamonds [the rarest and most pure]. The 910-carat rough we talked about earlier, the Lesotho Legend, is one. Knowing the origin of a stone doesn’t do away with risk completely, but it does make us more confident.

How much does a rough diamond generally yield in carats?

A quality rough diamond generally yields 40% to 45% of its original weight in polished stones and possibly as much as 50%, whereas some stones contain so many anomalies we can’t hope for more than 25% yield.

What do you do with the rest?

All that’s left is diamond dust which we use on the polishing mill and which serves to manufacture other diamonds. When I said we keep up to 50% of the rough, that includes everything, even the very small pavé diamonds.

Do customers request non-standard cuts?

Sometimes. We worked on a project with a Japanese firm that wanted square stones with specific faceting. We’ve also produced iconic cuts for jewellery houses, in fact we currently have a project for a large stone that will have an unusual shape, but that’s all I can tell you.

-

- Atours Mystérieux transformable necklace in white gold and rose gold, set with a 79.35-carat, D-FL Type IIa oval diamond, the largest stone cut from the Lesotho Legend. It sits at the centre of a double ribbon of Mystery Set rubies.

- ©Van Cleef & Arpels SA - 2022 by Marc de Groot

Some collectors buy jewellery as an investment and we know that value increases for jewellery that bears the signature of a famous house. Imagine a necklace set with a large diamond from an exceptional rough diamond. Would it command higher value than another stone with identical properties, because of its origin?

Yes, but not only. The history of the rough stone, which is documented, plays a part as does the heritage and creativity of the jewellery house that makes the finished piece. The customer is buying the work of a legacy jeweller but they are also acquiring a historic stone. There are collectors who follow certain houses’ collections for years on end. They invest a large part of their fortune in historic pieces that become part of their estate.

Do lab-grown diamonds pose a threat to natural diamonds in the way cultured pearls did for natural pearls when Mikimoto introduced them at the end of the nineteenth century?

Saying no would be to deny reality, but we should remember that a diamond can be a hundred-dollar ring from Wal-Mart or a 439-carat rough stone. The product is the same. The question should really be, what type of diamond competes with lab-grown? What category of product are we talking about and what type of clientele might consider a lab-grown diamond as a genuine alternative? One of the conversations around lab-grown diamonds, for example, concerns carbon emissions. Some people say they would rather purchase a lab-grown diamond because it has a lower environmental impact but that’s a mistaken belief. The lab-grown diamond industry is far from being a clean technology.

-

- The Queen of Kalahari, a rare 342-carat diamond, yielded 23 stones which became Chopard’s most precious jewellery collection to date: The Garden of Kalahari.

- ©Chopard

Are they competition for you?

Imagine someone has between a thousand and two thousand euros to spend on a diamond. Lab-grown would be an interesting option as it would mean a much larger stone and probably one with better clarity than a natural diamond for the same price. If, on the other hand, that person is a collector, I don’t see them wanting to buy lab-grown. As a sightholder, we get to view not just rare rough diamonds but also stones destined for wholesalers or manufacturers that work with lower-quality products, and there has been a real shake-up of prices for diamonds in this category, which compete directly with lab-grown. This is why we prefer to focus on top quality. I’ve yet to hear any of the leading jewellers express the wish to switch to lab-grown. Some brands have but they’re not in the same league. Fifteen years ago, the leading jewellery houses represented 15% of our revenue. Now it’s practically three quarters. So we’re not really in competition with lab-grown, although I can’t say it will never happen. I don’t have a crystal ball.

Is it always possible to tell a natural diamond from lab-grown?

Under the loupe, it would be practically impossible but with testing equipment we can see that a natural diamond has a different crystal structure. A natural stone’s growth lines go in all directions whereas a lab-grown stone is produced in successive layers and will have parallel growth lines. A 500-square-metre floor at our headquarters in Antwerp is set aside for sorting and screening small stones, including microscopic ones, to determine that they are natural. We deliver them to our customers in tamperproof bags. Our customers expect us to screen 100% of the products we supply and we have to be certain that no lab-grown stones have been accidentally mixed in with natural stones. We also remove what we call non-determined stones. These aren’t necessarily lab-grown but we can’t immediately determine that they are natural. Seeing this makes me think there is a future for natural diamonds and this will probably be in high jewellery.